Reading time: about 7 minutes

IOn the morning of 11 May 1940, the air-raid alarm sounded on Terschelling. Three German fighter planes had been spotted. One of them was shot down. The aircraft crew was fished out of the sea and brought ashore, making them the first Germans on the isolated Wadden island. Somewhat later, on 16 May, the freighter SS de Vliestroom dropped off a group of German quartermasters on the quay of Terschelling.

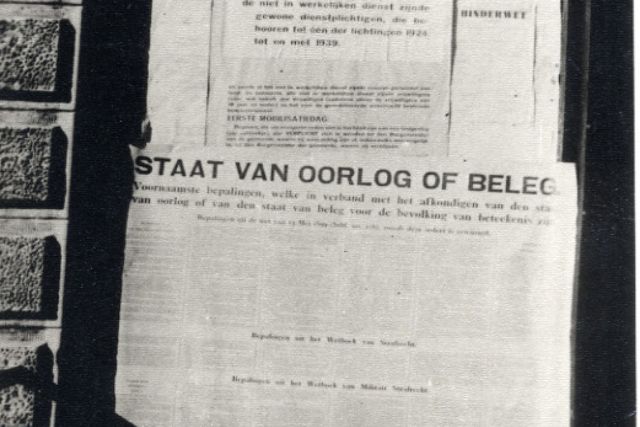

On 16 May 1940, the first Germans set foot on Terschelling. This was preceded by a period of uncertainty. Martial law was declared on 28 August 1939 by a notice in the window of the West-Terschelling town hall.

At the pilotage office, the Dutch flag was replaced by the swastika flag. This was also the case at the Brandaris lighthouse. The occupation of Terschelling was now a fact. All Dutch military personnel on Terschelling were taken as prisoners of war. In early June, they were allowed to return home to the mainland, where they were immediately mobilised.

Terschelling was of strategic importance to the Germans to deflect allied actions on or above the North Sea. Initially, 40 troops came to the island. But eventually, to meet the needs at the time, the occupying forces on the island grew to 1,200 and later to 2,000 units. The majority were navy and air force. German navy soldiers occupied the anti-aircraft batteries on the western and eastern points of the island. Sturdy bunkers, often combined with radar installations, were later added to the western anti-aircraft battery. This provided the German air force with an important detection tool.

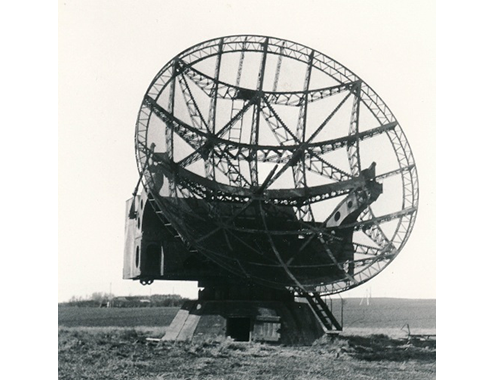

The radar installations, installed during the Winterausbauprogramm of 1942-1943, played an important role in the air battle between the Germans and the allied troops. The innovative ‘listening posts’ allowed the Germans to detect aircraft at a great distance. The first radar installation was placed on the Seinpaalduin near West-Terschelling, adjacent to the navy anti-aircraft battery. As part of their defence strategy, the Germans also built a radar installation on the Groenplak, northeast of the village of West-Terschelling.

Würzburg Riese (Giant Würzburg) radar

Defenceless above the North Sea and the Wadden Sea

The anti-aircraft batteries on Terschelling were often used during the war. The anti-aircraft artillery and the German fighter planes formed a notorious threat to the allied planes above the North Sea and the Wadden Sea. Individual planes were particularly vulnerable. For this reason, the Allied Forces soon decided only to fly towards Germany in closed formations, thus making the German fighters less effective. But it increased the chances of the anti-aircraft artillery hitting their targets. It made it as easy as shooting fish in a barrel.

Flying fortress makes emergency landing

On 4 February 1943, German Messerschmitts were persistently chasing the Texas Bronco, an American ‘flying fortress’ bomber. The plane, hit by German anti-aircraft fire, was an easy prey. The pilot made an emergency landing on Terschelling and succeeded in stopping the plane near post 7. Two crew members lost their lives and the other 8 were taken prisoner by the Germans.

‘Like a rock’

On the night of 3 October 1943, Terschelling was startled by a low-flying bomber, the Halifax DK203. It was damaged by German fighter planes on its return to England from Germany. Eyewitnesses saw the Halifax, lit up like a torch, approach above Oosterend and Hoorn only to crash near Arns shortly after. The Norwegian pilot and the tail gunner perished and were buried on Terschelling.

Terschelling also suffered the consequences of the battle at sea in various ways. On 5 October 1940, the SS Ottoland sailed onto a mine. The ship sank. Captain Haye Tichelaar - Harlinger by birth but a resident of Terschelling since 1962 - and his crew survived the ordeal. In March 1941, motor tanker Mijdrecht with her Terschellinger captain, Jan Swart, heroically fought German submarines. The ship was part of a convoy on its way from Scotland to America. Jan Swart received several high distinctions after the war, including the Nederlandse Bronzen Kruis (Bronze Cross of the Kingdom of the Netherlands).

Watery grave for 43 Terschellingers

On 30 August 1941, the ‘Winterswijk’ suffered a direct hit. The ship, carrying phosphate, was part of a convoy sailing from eastern Canada to Great Britain. First mate Douwe van der Moolen miraculously survived the attack. He was born on Terschelling. His captain, Jan de Groot, who was married to a woman from Terschelling, and 20 other crew members were never found. A total of 43 Terschellingers lost their lives at sea during the war years.

In a short period of time, the German army regiments transformed Terschelling into an impressive bastion of the Atlantic Wall. First with the help of volunteering islanders. But the Germans were soon short on manpower, so they started transporting labourers from the mainland to the Wadden island, at that time still part of North Holland.

Everything from machine gun nests and ammunition bunkers to the heavy Tigerstelling. The Germans relied heavily on the men from Terschelling for the construction of the Atlantic Wall. Those same men later witnessed the damage that was incurred from those fortifications, Piet Kaspers remembers.

Code name: Tiger

The most important addition to the Atlantic Wall on Terschelling was the Tigerstelling, to the east of West-Terschelling. It consisted of 2 sturdy bunkers for anti-aircraft artillery (Flak artillery), 2 bomb-resistant crew bunkers and 85 buildings to protect against shrapnel. Inside Bertha, the central bunker, the nerve centre for the analysis of flight patterns was located. This sturdy bunker became one of the Atlantic Wall programme's standard designs. The Tigerstelling, equipped with various radar installations, played an important part in intercepting allied aircraft.

The command bunker on the Tigerstelling, the nerve centre for the air battle above the North Sea and the Wadden Sea.

‘My first confrontation with death’

From their fortifications, the Germans had an iron grip on the movements on and above the sea around Terschelling. There were many victims. The injured and the dead were brought to the island, confronting the residents of Terschelling with the true horrors of war. For many young people, this was their first confrontation with death, says Gerrit van Leunen.

Initially, the occupation did not affect daily life on Terschelling all that much. Just like all the other Wadden islands, an Inselkommandant, namely Commander at Sea Helmut Klett, was appointed to Terschelling. He was the first of seven. Klett’s regime was rather lenient and there was little tension on the island.

Isolation

Tourism businesses picked up where they left off and started preparing for the next summer season with lots of holidaymakers. But this was too much for the German commander. In August 1940, he declared that the island could only be visited with his explicit permission. This isolated the residents of Terschelling.

Restricted area

Terschelling became a largely restricted area. This was not only a severe blow to tourism; the residents also lost a great deal of their freedom because large parts of the island were now ‘off limits’.

Billeting of German soldiers

Daily home life changed on Terschelling as well. During the first phase, before the bunkers were built, many families had to take German military personnel into their homes. The most comfortable hotels on Terschelling were ordered to provide accommodations to German officers. The atmosphere was rather friendly, very ‘island-like’, according to Gré Botje of Hotel Oepkes.

The resistance

As the war went on and the German regime in the Netherlands became more forceful, relationships cooled. However, the circumstances did not allow for active acts of resistance. Freedom of movement was extremely limited and more than 1,200 German military personnel were stationed on the island. With a population of around 3,300 inhabitants, this meant one German for every two to three Terschellingers. Escape was also impossible.

In 1943, preparing for the transfer of power after the victory of the Allied Forces, two resistance groups were formed but they never led to any real acts of resistance, such as sabotage. The risk of retaliation was just too great. The few incidents that did occur were negligible.

On 17 April 1945, the Inselkommandant ordered 12 inhabitants of Terschelling to be imprisoned on suspicions of aiding the resistance. This was probably a reaction to the tall tales about acts of revenge carried out by members of the resistance on the mainland that had reached the Germans on the island. After the liberation on 5 May, armed Germans still patrolled the island and a few incidents did occur.

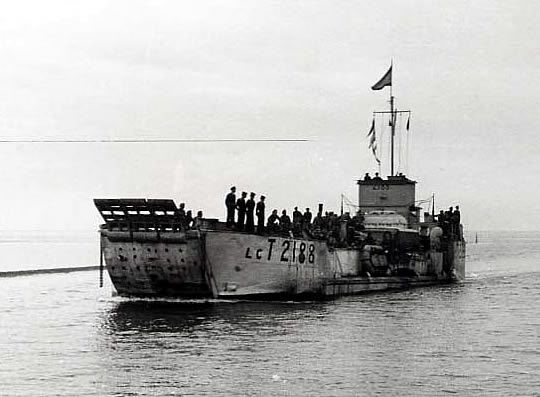

The islanders were fed up with the occupying forces but there was still no help from the mainland. The Canadians, who liberated the north of the Netherlands, felt they had already sacrificed enough. It was not until 21 May 1945 that the first British and Canadians set foot on the island. On 29 May, the Germans officially surrendered to the British troops that had arrived on Terschelling on two ships. The Germans were disarmed, and they left for Bremerhaven on several ships. The last German soldier left Terschelling on 5 June.

After 5 years of occupation, the Germans prepare to leave Terschelling.

Stichting Bunkerbehoud Terschelling is responsible for the former German radar installation, Tiger. This is one of the few fortifications in the Netherlands that has remained largely intact. The 7-hectare complex consists of more than 100 bunkers, where around 200 German soldiers lived and worked during WWII. Due to its impressive size, Bertha is unique in the Netherlands.

Visit Terschelling