For more than 35 years, Bram van Dijk has been searching for living relatives of pilots who are buried on Texel. This has led to impressive stories and wonderful encounters with people from various countries. Since 2004, Jan Nieuwenhuis has been researching crashed planes and collecting his findings together with Van Dijk's, in a comprehensible database. The two men complement each other perfectly and together they make sure that the stories of the pilots and their relatives are being told at the War and Aviation Museum on Texel.

It all started in November 1942, when the then 4-year-old Bram van Dijk was travelling on the back of his parents' bike to his grandmother who lived in the Prins Hendrikpolder. Below the dike, they passed the wreck of a plane that had crashed the previous day. A couple of German soldiers standing guard pointed out some small black heaps in the fields to them. Those were the eight casualties. “I have never forgotten that image. I have asked a lot of people about this, but I've never been able to find out the true story or the date,” Van Dijk says. Until 40 years later.

Bram van Dijk and Jan Nieuwenhuis

“Around 1985, I was home recovering from an operation. I was bored and decided to visit the war cemetery in Den Burg. There I wrote down the names of all 123 identified military men, mostly pilots, and their date of death. Among them, I found a crew member who had died on 9 November 1942. In the archives at the town hall, the crash site was reported as being Nieuweschild.” After this find, Van Dijk wanted to find out more about the other airmen who are buried on Texel as well as try to find and contact their relatives.

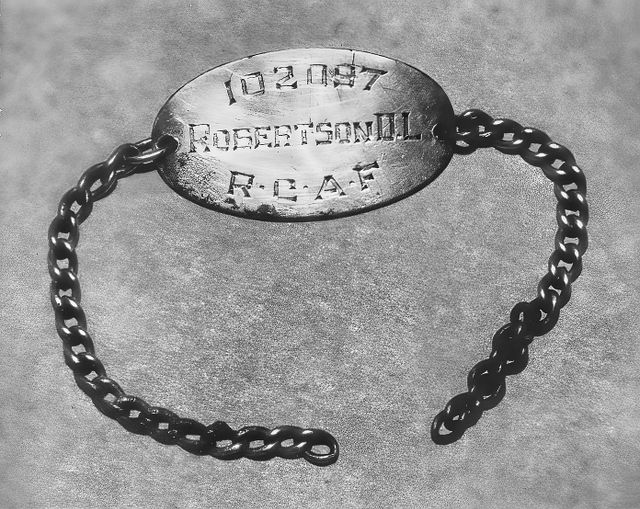

In 1989, divers were exploring the wreck of a crashed Lancaster bomber in the sea near Texel. “Back then that was still allowed. Now it 's forbidden because there are often bodies of airmen still in the wrecks. These wrecks have been classified as protected nautical graves,” Van Dijk explains. The divers found a lot of stuff, including a large amount of ammunition. “And among that ammunition we found a bracelet with the name ‘Roberston D.L.’. I found the pilot's relatives in 1991. They were very grateful that I had contacted them. Two years later I went to visit them in Hazlet, Saskatchewan in Canada.”

There was no internet when Van Dijk started his search. However, he did have a list of names of perished airmen, including place names. He also had a list of local papers and magazines. He took out adds in those. He often succeeded in contacting relatives via via. So far he has managed to trace the relatives of approximately 80 of the 123 identified military men who are buried on Texel.

But sometimes it happens the other way around. “Last year, we managed to contact the relatives of a Jewish pilot named Abrahams. I had never been able to trace his family members. But Jan Nieuwenhuis visited the cemetery and noticed that someone had left flowers and a picture at Abrahams's grave.” Nieuwenhuis continues: “Luckily, they had also written something in the cemetery guest book. Through this information, I was able to track down his niece. She, as a representative of the family, had come to Texel for one day to visit the grave. The niece said that Abrahams had been the second youngest of fourteen children: seven girls and seven boys. She was unaware of the existence of the museum. But as soon as she's able, she will be returning to Texel to visit the museum too.”

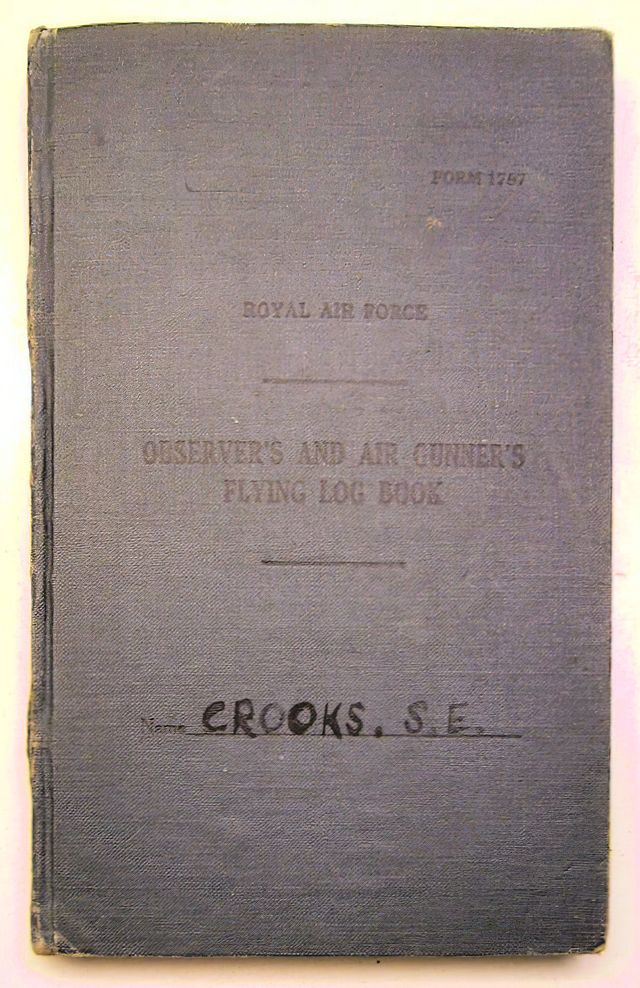

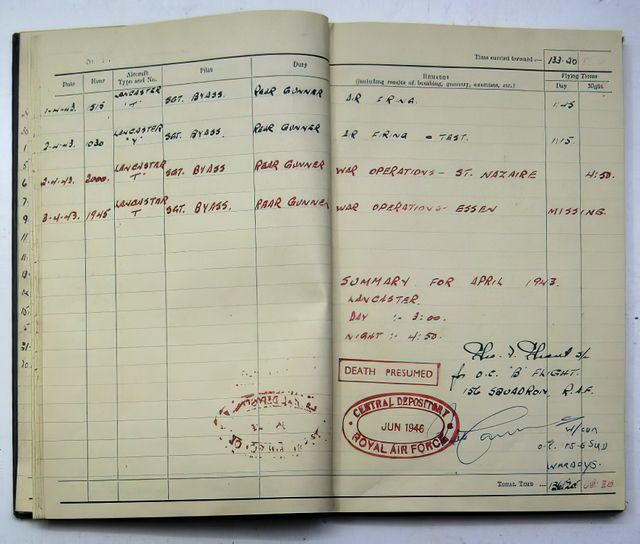

Over the years, Bram van Dijk has gathered many valuable (international) contacts which have resulted in a lot of extraordinary stories. “Almost everyone from the first generation has passed away now, so I am mainly in contact with the second generation. Children of airmen are very interested in what their fathers have done. But the younger generation also wants to know what happened. Many of them come to Texel to see it with their own eyes.” Family members ask Van Dijk for information, and he gets a lot in return as well. “Relatives send me photos, but also medals and uniform jackets. We even received a logbook from the sister of a pilot who washed ashore on Wieringen.” All these things are kept at the War and Aviation Museum on Texel and are used in expositions. So the stories of the airmen are kept alive and passed on to new generations.

Jan Nieuwenhuis began as a volunteer at the museum in 2004. “Bram had already been looking for relatives for some time. I was also interested in finding information about aeroplanes that had crashed and their crew. And with my background in IT, I knew how to enter everything into a database.” And he did. All the information that Van Dijk had already collected along with the discoveries of Nieuwenhuis were entered into one database. “At first, this only included the Wadden area, but people quickly began asking for other locations, such as the provinces of Friesland and Groningen. So it got bigger and bigger.” Nieuwenhuis’s research area now covers all of the Netherlands, the North Sea and the Channel. The database is regularly updated/adapted with new information and now contains detailed data from more than 1700 plane crashes.

See for yourself at: www.airwar4045.nl