In the autumn of 1940, the Germans lost the famous Battle of Britain and the British air force began a nightly bombing offensive on Germany. Initially, these bombings of German cities and the war factories were carried out with relatively small attack formations of just a few dozen aircraft. As the war continued, this steadily grew into a devastating air offensive with hundreds of four-engine heavy bombers destroying German cities almost every night; and killing thousands.

The British bomber formations mostly flew over the IJsselmeer and the Wadden area on their way to and from their targets, as they assumed the German anti-aircraft defence was weaker above the sea than above land. The navigation points along the Wadden islands were also easier to recognise than those on the blacked-out mainland.

To prevent the British bombers from reaching Germany, the Germans decided as early as 1940 to install a strong and forward anti-aircraft defence line in the Netherlands and to shoot down as many enemies as possible in this Vorfeld. From the second half of 1940, they began building radar stations along the Wadden coast to detect allied aircraft and guide their own fighter planes. In the Dutch hinterland - such as in Leeuwarden - large airports for German fighter planes were built. The radar sectors were all given code names that referred to the animal kingdom: Schlei (tench, a freshwater fish) on Schiermonnikoog and Tiger on Terschelling.

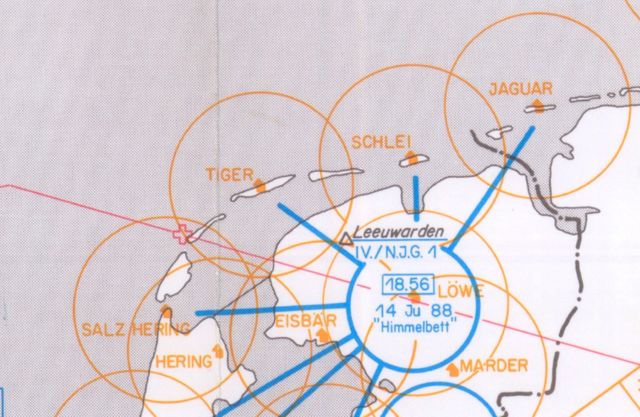

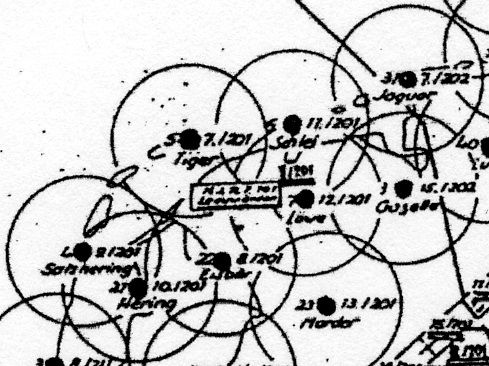

Map of the German radar belt in the Dutch Wadden area, April 1943. The radar stations Hering (Medemblik), Salzhering (Den Helder), Tiger (Terschelling), Schlei (Schiermonnikoog), Löwe (Marum), Eisbär (Lemmer), Gazelle (Veendam) and Jaguar (on the German Wadden island Juist) covered the entire Dutch Wadden area. Every allied plane that entered the Wadden area was tracked by the German ground radar's electronic eye and could be intercepted by a German fighter plane at any time. (Coll. BA/MA, RL 884)

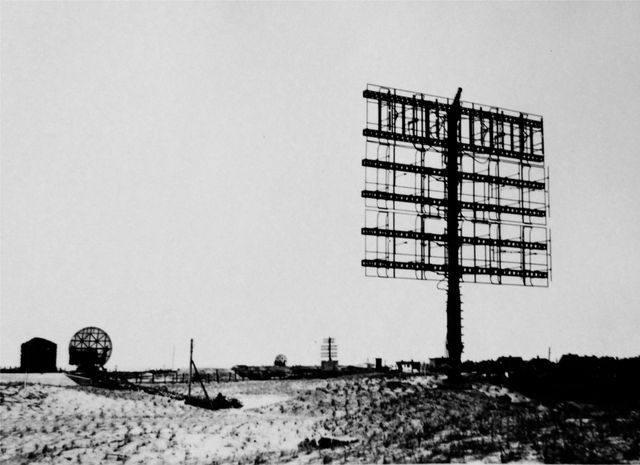

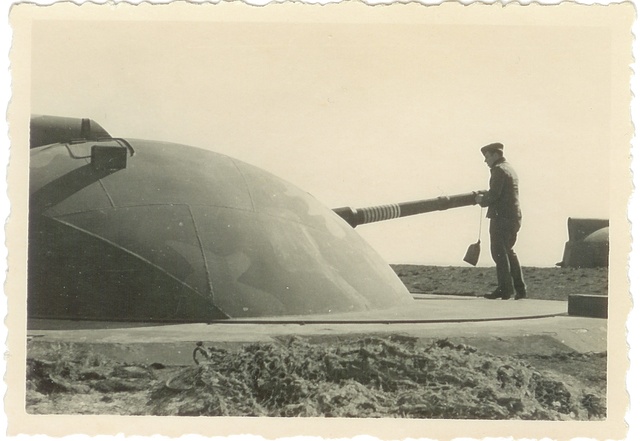

The installation of a German radar station in the Nachtjagd, identical to the Schlei and Tiger. On the left and in the middle, 2 Würzburg-Riese radars to track planes at short range, on the right a Freya radar for long-range tracking. With the help of these radars, the exact altitude and distance to the British bombers were determined and German night fighters were guided towards the enemy via radio contact with the commander in charge of the sector. (Coll. Carsten Petersen)

In this formidable and highly feared by British bomber crews nightly defence line, the Nachtjagd (night fighters) took down hundreds of planes between 1941 and the middle of 1943. It is estimated that the night fighters that patrolled radar sectors Schlei and Tiger alone took down 168 bombers, costing the lives of at least 800 crew members.

In the summer of 1943, the English succeeded in taking out all the German air defence radars at once by throwing out Windows, millions of aluminium strips that jammed radar reception. This pulled the legs out from under the nightly anti-aircraft defence in the Wadden area, largely ending the strategic role of the Nachtjagd in this region.

The strategic air battle in Western Europe against Germany was purely a British-German conflict until early 1943. From February 1943 on, the American air force also carried out bombings on the German war industry during the day, establishing a ‘round the clock’ offensive on Germany; the Brits by night and the Americans by day. This lasted until the German surrender in May 1945. Just like the British, the Americans often flew over the Wadden area on their way to Germany and from early 1943, many air battles were fought in this area by day between the German Tagjagd (daytime fighters) and the American Combat Boxes.

The Messerschmitt Bf110, the standard night fighter deployed in the Wadden area between 1940 and 1943. This aircraft probably belongs to II./NJG1, the unit that successfully operated in the Wadden area out of Leeuwarden and Bergen-aan-Zee. On the nose of the plane, the coat of arms of the Nachtjagd is visible, a German eagle striking into the heart of England. (Coll. Wim Govaerts)

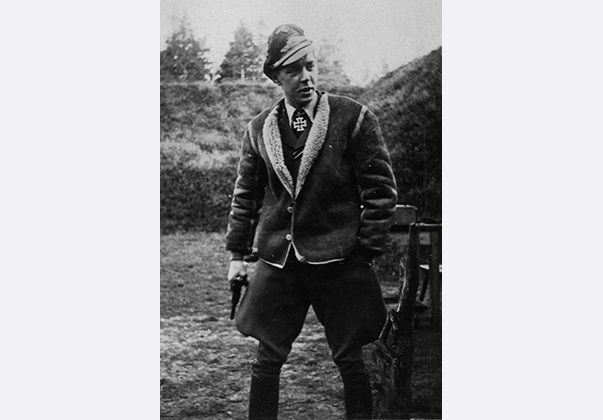

One of the German Nachtjagd ‘aces’ who achieved many successes in the nightly battles in the Wadden area between 1941 and 1943 was Major Helmut Lent. He managed to gun down 110 aeroplanes before dying in a plane crash on 7 October 1944. Among those were 26 bombers that he took down in the Dutch Wadden area, flying out of Leeuwarden. Half of these victories are estimated to have been won in the Tiger radar sector; the others in Löwe (3), Salzhering (1), Schlei (6) and Eisbär (3). (Coll. Lieuwe Boonstra)

In 1941, radar installations were built on two of the Dutch Wadden islands to track invading allied bombers and guide German night fighters. In the summer of 1941, the Tiger sector was built on Terschelling and in the spring of 1941, the Schlei (tench) sector was built on Schiermonnikoog. Both radar stations were equipped with a Freya radar to track enemy planes, and from 1942 on, also with two Würzburg precision radars for tracking enemy bombers and their own fighters at short range. From the middle of 1942, the Tiger was enhanced with two Wassermann radars, making it possible to detect allied planes from a distance of 300 kilometres.

As the nightly air battles went on, the Tiger would become one of the most successful ground radar stations in the whole of occupied Europe. Led by the commander of sector Tiger, an estimated 120 bombers were shot down by night fighters between September 1941 and July 1944, most of them disappeared in the marshlands of the Wadden or the North Sea.

The events that took place during the night of 19 and 20 February 1943, are typical of an average night on which British bombers flew over the Wadden area. On that night, 338 bombers were sent to Wilhelmshaven where they dropped their bombs for a period of 40 minutes. 12 of those planes never returned. Despite the bad weather, more than 50 night fighters were patrolling northwest Germany and the Wadden area. 11 of them fought the bombers and 9 British planes were shot down, all of them on their way back to England. 6 of them were taken down by 3 night fighters from the airbase in Leeuwarden in the Dutch Wadden area; half in sector Schlei and the other half in sector Tiger.

First lieutenant (Oberleutenant) Hans-Joachim Jabs, the commander of 11./NJG1, shot down 3 Short Stirlings from the 15th Squadron in 44 minutes in Schlei under the command of Oberleutenant Maier. The bombers all crashed into the North Sea, 5 km north of Ameland, 10 km west of Schiermonnikoog, and 45 km north of Terschelling. These were Jabs’s 20th to 22nd victories and Maier’s 53rd to 55th. None of the bomber crew survived; 52 men died in the icy cold North Sea near Ameland, Vlieland, Schiermonnikoog, Terschelling and Texel. Most of them are still registered as missing in action.

In the operations room at Leeuwarden airbase, the Nachtjagd crew receive instructions about operations for the coming night, sometime during the first half of 1942. OLt. Lent, the Gruppenkommandeur of II./NJG2 on the left, and next to him - then commissioned officer - Gildner. The crew wore different types of life vests when patrolling above the North Sea. (Coll. Rob de Visser)

Oberleutenant Paul Gildner, commander of 1./NJG1, had two victories (his 42nd and 43rd), under the direction of Tiger on Terschelling. Commissioned officer (Uffz.) Heinz Huhn, Gildner's radar operator, wrote in his diary:

"We're waiting in the Operations room tonight (the room where flying operations are coordinated). The mist outside is thick and ground visibility is low. We're receiving reports of enemy planes on their way to Wilhelmshaven. But due to the bad weather, we can't take off and pursue them. Gildner wants to try anyway, he wants to use the old but very stable Dornier. The bombers will pass through the radar belt in our area on their way back. We decide to roll the dice and take off. A full moon is visible above the thick mist. The Dornier is not equipped with flame tamers on the engine exhausts, so flames can be seen coming out of the exhausts. The radio and radar equipment in the plane are worn out. So, I turn off the Lichtenstein onboard radar and we're forced to search with the naked eye. We immediately receive the order to fly a patrol in Tiger. The first 'courier' (code word for British bomber) is a Halifax. The British crew probably feel safe above the sea and are not expecting an attack. Gildner starts the attack, the courier catches fire and crashes into the North Sea at 9:05 pm. Sieg Heil.

By now, the crosshairs are shattered and only one cannon is still operational. Ground control sends us after another plane. We spot it at 9:10 p.m. Another Halifax. In the background, a thick column of smoke caused by our first Abschuss can still be seen rising up from the water. One attack, the courier starts spewing smoke, explodes and crashes into the water. The time is 9:16 pm.

“ Our plane’s propellers were hit by enemy fire ”

Ground control from Tiger guides us towards a third aircraft, an American Boeing this time. The radio connection with Tiger is bad because one of the ground transmitters has stopped working. I feel sweat dripping down my entire body, I'm constantly flipping switches and tinkering with the onboard radio in the hope of receiving some messages. And my helmet is way too tight. Despite all this misery, we're able to maintain visual contact with the enemy bomber. We move into attack position. Gildner opens fire, but only 3 of our machine guns are still operational, and none of our cannons. Our enemy hasn’t caught on fire yet. We make another attempt and fire some shots, but we have to abort the attack because a second courier has arrived just 200 metres from us. So, our third enemy gets away and we can only report him as being damaged. Our plane’s propellers are hit by enemy fire.

We return home immediately and land safe and sound. Later that night, a big celebration is held in the Operations room, with champagne and red wine. Jabs took down 3 bombers, all 3 Short Stirlings. Our third opponent sent out a distress signal and probably didn’t make it back to England.”

Paul Gildners died just 5 nights later near the Gilze-Rijen airport in Brabant when one of the engines of his Messerschmitt 110 caught on fire and the plane crashed.

A Dornier Do215 B-5 night fighter at the Leeuwarden airport in the summer of 1942. (Coll. Helmut Conradi)

Fw. Heinz Vinke, here in the summer of 1943 standing in between his gunner Uffz. Johann Gaa (left) and radio/radar operator Fw. Karl Schödl (right), had at least 11 Nachtjagd victories in the Wadden area, at least 4 of which were guided by Tiger. This crew was shot down by a British night fighter north of Borkum during the night of 17 to 18 August 1943. Vinke survived, but his 2 crew members are still missing. Heinz Vinke was saved after 18 hours of floating at sea in a small rubber boat; he perished 6 months later. (Coll. Rob de Visser)

The second Nachtjagd radar station built on a Dutch Wadden island was Schlei on Schiermonnikoog. Under Schlei guidance, an estimated 48 bombers were shot down by night fighters between June 1941 and July 1944. The night of 18 to 19 June 1941, brought the first victory for Schlei in the nightly air battles. Of the 100 British bombers sent to Bremen that night, 6 were shot down by night fighters. This was a triple hit for Schlei.

At seven minutes past midnight, commissioned officer (Offiziersanwärter - OA.) Paul Gildner, together with his regular crew (radio operator Uffz. Schlein and flight engineer Uffz. Poppelmeyer in Dornier Do215 B-5 G9+NM, was sent up from the airport in Leeuwarden to patrol in sector Schlei. Under the instructions of Leutnant (Lt.) Schultze, the Jägerleitoffizier or the hunt leader on the ground in Schlei, Gildner shot down 3 bombers near Ameland in less than an hour; his 12th, 13th and 14th war victories.

Paul Gildner wrote his report the next day:

“I received the order over the radio to assume a waiting position near Schiermonnikoog. After 2 hours in the air and several unsuccessful pursuits of enemy planes, I spotted a Wellington flying at an altitude of 4,200 metres. At approximately 1:58 am, I attacked the plane and shot from close range from underneath and behind. My opponent hadn’t noticed me. My first attack was immediately successful: the plane caught fire, went into a vertical dive and crashed into the Wadden Sea near the eastern point of Ameland. On 19 June at 2:00 pm, 2 of the crew members were picked up by a border patrol near Holwerd. The other crew members were found dead.

(Gildner's first victim was the 300 Squadron Wellington W5665 with an entirely Polish crew. 4 men died and 2 were taken as prisoners of war).

“ One attack sufficed: the vessel’s hull and wings caught fire immediately ”

After my first victory, the ground radar officer guided me towards a few enemy planes, but without result. While I responded to an order from the ground ‘Plane approaching on the radar’, I could make out an opponent flying approximately a kilometre behind and 100 metres above me in the dusky skies. I immediately reported my visual to the ground station, that picked up the enemy on the radar and guided me towards him. I retained visual contact with my adversary and initiated an attack without waiting for orders from the ground. Because my opponent was flying west, towards the darker part of the sky, I lost visual contact for a moment. My flight engineer, Uffz. Poppelmeyer, had retained visual contact and told me his position. I identified the enemy plane as a Wellington and attacked it at 2:34 am at an altitude of 3,600 metres. One attack sufficed: the vessel’s hull and wings caught fire immediately. The tail gunner returned fire, but only for a short time: the Wellington exploded into numerous pieces that fell into the sea and floated around burning for a while, 57 kilometres north of Ameland. We didn’t see any parachutes, so no doubt the entire crew perished.

(This was the 301 Squadron Wellington R1365; the entire crew of 6 Polish airmen perished).

After my second win, ground control ordered: ‘Pay attention, new enemies approaching.’ I was directed north-north-east from where my second opponent had crashed. After that I heard: ‘Two enemies straight ahead of you’, I saw one of them flying about 500 metres in front of me and a little higher up than me. I recognised it as a Whitley. I took it down with one attack, coming from behind/underneath at an altitude of 2,200 metres, at 2:57 am. His left engine caught on fire and the Whitley spiralled downward, crashing into the sea and disappearing beneath the waves. This happened 47 kilometres north of Ameland. I wasn’t able to see what happened to the crew.”

(This was the 10 Squadron Whitley Z6671; last radio contact with this plane from England was at 02:50 am, 7 minutes before Gildner struck. The five-headed crew is still missing).

A drawing from the war that shows a Messerschmitt 110 night fighter shooting down a Wellington into the sea. (Coll. Helmut Conradi)

The air battle near Texel, 4 February 1943

While the German night fighters had their hands full fighting the nightly British bombings, Germany was confronted with a new threat from the skies for the first time on 27 January 1943. That day, the 8th American air force carried out its first strategic bombing of a German city. The Germans did not have enough day fighters to counter this threat, so they had to deploy their night fighters during the day against the Americans. The first time was on 4 February 1943 in the Dutch Wadden area. The Americans bombed Emden that day. OLt. Hans-Joachim Jabs, a highly decorated veteran from the Battle of Britain in 1940, who now flew night fighters in IV./NJG1 from the Leeuwarden airbase, guided 8 Bf110 night fighters from Leeuwarden to intercept the B-17 'Flying Fortresses'.

The German night fighters were guided from the ground by radar installations Eisbär, Löwe and Tiger. Shortly after 12:00 pm, they spotted the Americans near Emden - on their return to England - and pursued them over the Wadden islands. By then, the Americans had been doing battle for half an hour with single-engine Tagjäger (day fighters); between 11:27 am and 12:40 pm they reported 7 B-17 Abschüsse, near Den Helder, Leer and Texel.

Even at full speed - to be able to catch up to the fast bombers - it took them until they reached the air space above Ameland before the first Messerschmitt could initiate an attack. In the battle that followed, somewhere between Ameland and Texel, the night fighters claimed to have shot down 3 Flying Fortresses between 12:25 pm and 12:51 pm; at 12:52 pm, the night fighters aborted the attack and returned to their Frisian home base. All of them had been badly damaged by returning fire from the Americans and 2 had to make emergency landings.

Gefr. Erich Handke, radio/radar operator in the Nachtjagd crew of Uffz. Georg 'Schorsch' Kraft, remembers this from his 7th operational flight:

“When the bombers were returning home, we started off in 4 pairs to intercept a formation of 60 Boeing ‘Flying Fortresses’. Uffz. Naumann (together with his radio/radar operator Uffz. Bärwolf) claimed their first victory. As part of a pair (together with Lt. Völlkopf), he attacked the formation head-on and managed to damage a Boeing, forcing it to leave the protection of its formation with a smoking engine and its landing gear lowered. Naumann immediately turned around and attacked again, this time from behind. As a result, both machines went down engulfed in flames, but Naumann managed to make an emergency landing on the North Sea beach of Ameland. Hptm. Jabs, who had been awarded the Iron Cross for his 15 victories above England in 1940, also took down a Boeing, together with his wingman. Uffz. Scherer attacked alone. He announced over the radio: ‘I have contact with 50 ‘couriers’ and am about to attack’. After that he dove from the top of the formation, taking enemy fire from all sides. He did manage to fire at one bomber but was forced to abort the attack because his face was filled with grenade shrapnel and Mehnert, his radio/radar operator, had been hit in the face by his shattered altitude meter.

“ He was forced to abort the attack because his face was filled with grenade shrapnel ”

And then it was OA. Grimm’s and our turn. We received our instructions from radar station ‘Eisbär’ and were the last to reach the enemy formation, at an altitude of 7 km and 20 km west of Texel. Suddenly, we saw 60 Boeings flying ahead of us! I have to admit that I shuddered with fear at the sight of those planes. My comrades had the same reaction. We were tiny in comparison to these ‘Flying Fortresses’. We attacked from the flank and targeted the formation leader first. But my pilot turned too fast and we didn’t get a chance to fire at the planes, passing behind the formation instead. This attracted all their fire. So, we decided to attack the last plane in the formation, until we and our Flügelmann had used up all of our ammunition. During Grimm's last attack, a Boeing caught fire; it went down and crashed. The Perspex windows in Grimm's Messerschmitt were all destroyed, his radio/radar operator Uffz. Meissner was wounded and their left engine died. We were also forced to switch off our damaged, smoking left engine. Both of our left fuel tanks and the rear tank on the right were perforated and the fuel lines, cooling liquid lines and Schorsch’s armoured windshield were all ‘kaputt’. So we flew back to Leeuwarden, each with one functioning motor. Then Grimm’s only operational motor died too, forcing him to make an emergency landing; our motor lasted until after we had landed. We landed next to Grimm, leaving a trail of smoke behind us.”

A total of 5 American B-17 Flying Fortresses were destroyed in the air battle, 31 crew members died and 19 were taken as prisoners of war.

There’s an interesting side note to the story of 4 February 1943, with a link to the story of the battle for the convoy routes in the Wadden area. 2 of the American bombers that did not succeed in reaching their targets dropped their 22, 500-pound bombs on a German maritime convoy north of Vlieland, as an alternative target. These bombs missed their targets.

The Messerschmitt Bf110 of Uffz. Alfred Naumann burning on the North Sea beach of Ameland on 4 February 1943, with one of the crew members posing for the camera. (Coll. Ab A. Jansen)

Hptm. Hans-Joachim Jabs. In addition to his daytime victory on 4 February 1943, Jabs also shot down 12 bombers at night in the Wadden area in 1943. 5 of them guided by Tiger and 4 in Schlei. (Coll. NeunundzwanzigSechs Verlag)

1 of the 5 Flying Fortresses taken down on 4 February 1943 was the B-17 F ‘Memphis Tot’ from the 427 Bomb Squadron/303 Bomb Group. 3 crew members died in the attack. The tail is buried halfway into the Wadden, approximately 8 km northeast of Den Helder. (Coll. Rob de Visser)

Convoy strikes and Gardeners in the Wad

The battle for the German maritime convoy routes

Read more →