In addition to air defence lines with fighter planes and the Luftwaffe radar installations, the German Kriegsmarine (War Navy) constructed a series of anti-aircraft artillery batteries and searchlights along the Wadden coast in the summer of 1940. Their primary goal was to fight the Allied bomber formations that were flying to and returning from Germany. They did this by shooting directly - with the help of radar or searchlights - at individual planes or attacking an entire group of bombers in staggered formation. The Flak searchlights were also able to spot individual bombers in their bright lights in the darkness of the night, which the patrolling night fighters could then attack.

The most important Marine Flak units on the islands of Vlieland to Schiermonnikoog was the Marine Flak Abteilung 246. Other Flak units were active on Texel and around Den Helder. From November 1940, the M. Flak Abt. 246 was operational on four islands. There were two batteries on Vlieland (3./M. Flak Abt. 246 Battery Vlieland West and 4./M. Flak Abt. 246 Battery Vlieland East), and on Terschelling (5./M. Flak Abt. 246 Battery Terschelling-West and 6./M. Flak Abt. 246 Battery Terschelling-East), one on Ameland (7./M. Flak Abt. 246 Battery Ameland) and one on Schiermonnikoog (2./M. Flak Abt. 246 Battery Schiermonnikoog). Headquarters and the 1./M. Flak Abt. 246 Stabsbatterie were located in Harlingen. There were another 11 Flak batteries on Texel and around Den Helder.

Geographic overview of German Flak units in the Dutch Wadden area. A total of 17 high-calibre Flak batteries that were constructed on the Wadden islands and in the area around Den Helder are clearly visible here. Four cannons were the standard for every battery. (Coll. NIOD, 1945 - Map of German Artillery in the Netherlands - CAD - Inspectie der Genie 1945 - 1955 box 20 no 11310)

Almost all batteries were equipped with heavy 10.5 cm calibre artillery, the diameter of the grenades that were fired. These cannons had a vertical reach of approximately 11 km and 17 km horizontal. To prevent direct air attacks on these batteries, several other lighter Flak cannons were always placed somewhere in the vicinity. A large command bunker was built in Den Helder from which the Marine Flak in this region was coordinated; the Flak defence of Vlieland to Schiermonnikoog was led from Harlingen.

A 10.5 cm cannon in rotating cement gun turret from the 4th battery of the M. Flak Abt. 808 on De Mok, Texel. The white rings around the cannon represent the number of Allied planes shot down by this cannon. (Coll. Hans Nauta)

Some anti-aircraft cannons stood on a standard cement foundation, sometimes in combination with a bunker. These are the so-called Regelbauten, designed by the German Festungpionieren and used along the entire Atlantic Wall. Construction methods were very diverse: sometimes the cement foundations had a steel gun turret, but not always. Each Flak battery had countless bunkers and smaller bunkers. The most important one was for the fire command (the Flakleitstand), and also, of course, for the grenades, crew, provisions, water, kitchen, mess hall, etc. The Commander of the Flakabteilung sat in a Flagruko (Flak Gruppen Kommandostand). In Den Helder, this was commonly known as the ‘Kroontjesbunker’ (Crown bunker) in the Grafelijkheidsduinen. Such a cement giant was not built in Harlingen, and the crew had to make do with just a large brick building. After three-quarters of a century, these constructions are still standing and remain an important part of the military heritage.

Several light calibre Luftwaffe Flak were also stationed around the Tiger and Schlei radar installations and near the defence around De Vlijt airport on Texel. In the Tiger Stellung on Terschelling, for example, six 2 cm Flak were installed by the end of the war for defence against low-flying Allied aircraft.

Between 1941 and 1944, the Flak batteries shot down an estimated 52 bombers by night in the Wadden area. 13 of those aircraft were shot down in collaboration with night fighters in the Tiger, Schlei and Eisbär sectors. Between 1943 and the Liberation in May 1945, the Flak was also active during the day as a defence against the American bomber formations that flew over the Wadden area. They took down several American heavy bombers.

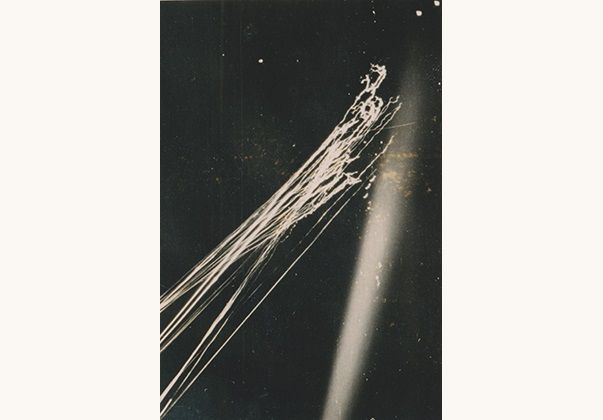

In searchlight and anti-aircraft fire. On Christmas Eve 1940, a British bomber is caught in a searchlight above the harbour of Den Helder and shot at by Flak. (Coll. Karl Köster).

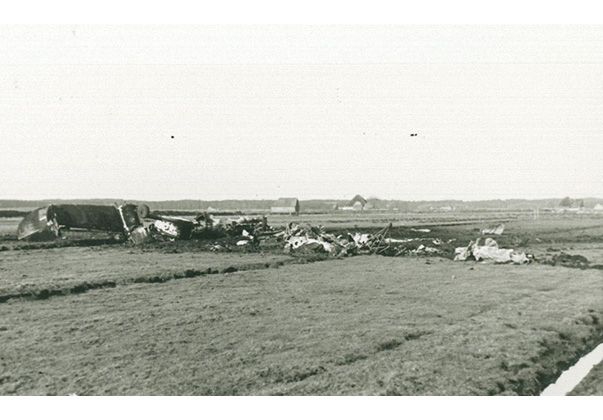

The wreck of the 44 Squadron Lancaster W4126 that, during a bombing mission to Nienburg on the evening of 17 December 1942, was shot by various navy ships and eight different Flak batteries on Texel and Den Helder. Only one crew member (out of seven) managed to jump out of the aeroplane with his parachute just before it crashed at 18:43 h near De Westen (Den Hoorn) on Texel, burning completely. (Coll. Wim Govaerts)

Two double Flak and Nachtjagd victories near Terschelling

To illustrate the collaboration between the German night fighters and Flak, but also as proof of the competition between them, we will recount the story of two double victories near Terschelling. During the night of 24 to 25 February 1942, 23 British bombers were sent to drop bombs along the Dutch Wadden islands. Between 20:53 h and 23:05 h, they 'planted' their magnetic mines on the convoy route. Approximately 10 German night fighter patrols flew as a defence against the minelayers, guided by the radar installations in the Dutch Wadden area. Among them were at least 3 Messerschmitt Bf110s from II./NJG2, patrolling out of the Leeuwarden airbase.

Portrait picture of OLt. Egmont Prinz zur Lippe-Weissenfeld, the Staffelkapitän (commander) of 5./NJG2. (Coll. Wim Govaerts)

Two minelayers, both Hampdens from the 144 Squadron, did not return. Both fell victim of Oblt. Prinz zur Lippe-Weissenfeld, an Austrian Nachtjagd 'ace' of noble descent who commanded the 5./NJG2. That night, Zur Lippe flew under guidance of the Tiger sector on Terschelling. His first victory that night (and his 16th in total) was the AT194, which crashed into the sea north of Terschelling at 21:49 h from an altitude of 300 metres. Just 13 minutes later, he claimed his second victim, the X2969, in the exact same area; upon his return to Leeuwarden, the night fighter reported that he managed to hit the Hampden at an altitude of 200 metres, after which the aircraft crashed into the sea, engulfed in flames. 7 of the 8 crew members are currently still missing; 1 of them washed ashore on the Danish coast and was buried in Lemvig.

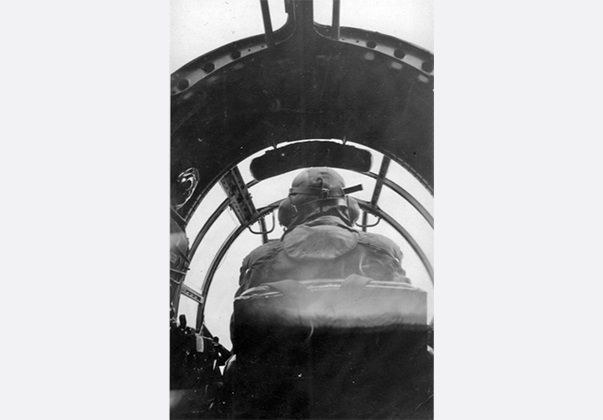

Flight Sergeant Lord Bruce Thomas Dundas, seen from the back, in the narrow cockpit of the 144 Squadron Hampden X2969. Lord Dundas of Orkney perished together with his crew in the X2969 on 24-25 February 1942. They are all still registered as missing in action. (Coll. Andy Bird)

A Marine Flak battery on Ameland, the 7./M. Flak Abt. 246, also claimed to have taken down both aircraft. In the War Journal of the M. Flak Abt. 246, this is described in great detail:

Ameland. 21:25 – 23:02 h alarm. At 21:42 h, firing at an enemy aircraft north of Ameland, flying in from the east, with 41 10.5 cm shells. Altitude 2,000 - 700 metres. Distance 4.9 – 4.2 – 9.5 kilometres. Target swerved north, after which a burning glow was visible above the clouds and the plane crashed into the sea at 21:43 h, burning heavily. At 22:03 h, shelling of a second enemy aircraft north of Ameland with 20 10.5 cm shells. Altitude 1,000 - 800 metres, distance 7.0 - 9.6 kilometres. A burning glow was observed falling into the water at 22:04 h.

During this alarm, the same Flak battery fired at another 3 Gardeners without observing any hits.

Whether or not Zur Lippe received part of the 'loot' is unknown. What is known, however, is that both Abschüsse were officially awarded to the Flak battery on Ameland by the concerned authorities on 26 March and 16 June 1942. Competition between different divisions of the armed forces was encouraged in the German military - for example, the Nachtjagd and Flak often fought heavily to be declared the shooter of a particular bomber or minelayer. In the case of 24-25 February 1942, it seems that the Marine Flak eventually won.

A Sterling bomber is loaded with six 1,500 pound magnetic mines, equipped with parachutes at the head. (Coll. S.A.A.)

Kriegsmarine Flak and night fighters take down 6 'gardeners' and a bomber in the Wadden area

During the night of 21 to 22 January 1943, a standard British Bomber Command operation took place in the middle phase of the war in the air. 82 aircraft were sent out to bomb Essen between 19:37 h and 20.03 h, while 70 aeroplanes dropped a few hundred magnetic mines on the shipping routes along the Wadden islands between 18:10 h and 19:43 h. 4 Lancasters never returned from Essen and 6 did not come back from the Gardening operation.

Despite the full moon that night, the German Nachtjagd was not able to put up a fight due to heavy clouds, rain and limited visibility along the bombers' flight routes. Only 10-15 night fighters patrolled against both threats, guided by the ground radars. They managed to take down a bomber and a minelayer in the Wadden area, while Flak destroyed 5 'gardeners' within a 45-minute time frame.

An 8.8 cm Flak cannon in action at night. (Coll. Horst Jeckel)

The first Flak victim was Wellington HE410 from the 466 Squadron. Between 18:00 h and 18:06 h, near Terschelling, it was damaged by hostile fire from the 5th battery of the M. Flak Abt. 246 (Terschelling-West), after which it set course for the Frisian mainland. It was hit again by a Flak and made an emergency landing near Wirdum at 18:20 h. One crew member was lost. 17 minutes later, a second Wellington, the BK432 from the 429 Squadron, was hit by Flak from Stab M. Flak Abt. 246 near Harlingen and exploded in the Wadden Sea near Roptazijl. At 18:58 h, a third Wellington (the BJ966 from the 420 Squadron or the X3873 427 Squadron) followed, caught in the searchlight near Borkum and shot down by Marine Flak, eventually crashing north of the island. Fifteen minutes later, a Halifax from the 76 or 158 Squadron was taken down by Flak near Wangerooge. Finally, a second Halifax from the 76 or 158 Squadron was caught in the searchlight near Borkum at 18:45 h, immediately attracting Flak fire. A minute later, it was also shot at by the night fighter Hptm. Prinz zur Lippe-Weissenfeld, which patrolled the Jaguar sector, disappearing into the sea near Borkum. All 30 crew members on board these 5 minelayers perished; only 3 of them have a known grave.

"We were the second fighter plane of the first patrols that were airborne; the first plane had already set off for Tiger (Terschelling). Schorsch climbed into the cockpit, ready for take-off; I stayed by the phone, waiting for further orders. Hptm. Ruppel (the head ground control officer of the Northern Netherlands) gave the order to fly to radar zone Hering (near Medemblik) and assigned a good runway to us. But then disaster struck: first the engines wouldn’t start, then both battery carriers and our on-board batteries were empty, but finally one of our engines started. Because all of this, we had lost at least six minutes. So, when we finally came rolling out of the hangar, our take-off orders had been cancelled, but we hadn’t heard that. Under normal circumstances, the pilot would contact the control tower to turn on the runway lights as soon as he started rolling towards it. But we couldn’t do this because our on-board battery was still dead, and our plane’s generators wouldn’t be able to start charging it until after take-off.

And so we took off in the dark, six minutes late, without permission or contact with the control tower, from the wrong runway (at 18:53 h)! To make matters worse, the wires in Schorsch’s flying helmet weren’t connected, so we weren’t able to talk to each other for the first three minutes until I figured out what was wrong and shouted this to him. Only then could I contact the control tower; they were astonished that we were airborne. One minute later Hptm. Ruppel decided we should patrol sector Salzhering (Den Helder) as we were up there anyway.

“ Being rookies, we didn’t really know what to do now ”

Once we'd reached Salzhering, we were able, with great difficulty and on the short-wave frequency, to contact the combat leader of this sector. We were ordered to intercept a returning enemy aircraft, but we soon lost contact with ground control because the Tommies were jamming our radio frequency. So, we missed the first interception. I also made the mistake of immediately switching on the transformer of my Lichtenstein on-board radar without giving the tubes time to warm up, so my radar was out of commission for the rest of the night. Fortunately, another British plane was crossing our sector and this time I managed, not without problems, to maintain radio contact with ground control, despite enemy interference. The moon was full, and our view was about 1.5 kilometres, so the lack of an on-board radar wasn’t a complete catastrophe. We also received excellent guidance from the ground. Because the enemy was flying at an altitude of 6,000 metres, we decided to fly at 5,800 metres. This way, Kraft was able to establish visual contact with the enemy at a distance of about 2 kilometres. However, it appeared to be flying 200 metres below our altitude, which meant that the large Würzburg radar in Salzhering had a deviation of around 400 metres, something we would experience almost never again. The Tommy also flew in a zigzag pattern and was constantly changing altitude. We sped towards it at full throttle.

Slowly but steadily we were able to make out the silhouette of the four-engine bomber. Being rookies, we didn’t really know what to do now, how to sneak up on the Tommy, and so we made all the rookie mistakes you could imagine. Instead of approaching it diagonally or from the side, we came up straight behind it. Given the good visibility, the tail gunner should've already spotted us long ago, but he may have been shook up and nauseous because of the constant zigzagging. Whatever the case, we approached undetected. I'd also forgotten to turn on the heating and to plot a course for after the attack. We identified the enemy as being a Lancaster.

When we were about 200 metres below the Lancaster, Schorsch pulled up way too abruptly. He ended up firing from 300 metres without doing any real damage - he'd only pushed the firing button down half-way, so he was only shooting out of four machine guns. This, of course, had woken up the Lancaster’s tail gunner and he returned fire, but the shots went over our heads because the bomber had started a steep evasive dive at the exact same moment. Schorsch immediately followed suit and kept firing. This time he did push down hard on the firing button, which also engaged the on-board canons. The Lancaster’s right wing exploded, but a second later we were engulfed by clouds coming in from the west. This made us lose sight of the burning bomber, in part because we now had our hands full with our own predicament.

“ Meanwhile, in the back, I was being tossed all over the place - and I was scared to death ”

The steep descent had caused our artificial horizon to go haywire, causing us to effectively lose our most important flight monitor. We had also misjudged our dive in the clouds and we rapidly lost 2,000 metres of altitude. Only when we got down to 3,400 metres, our plane levelled out by itself, still surrounded by clouds. We gradually climbed again for the next couple of minutes, until Schorsch finally regained control of the plane. Meanwhile, in the back, I was being tossed all over the place, and I was scared to death - we were out at sea, 40 kilometres from the coast. Schorsch had also had more than enough. We finally checked if both engines were still operational and tried to figure out how to explain to ground control that we had shot at an enemy aircraft without taking it down. There was nothing worse than having to report to Hptm. that we had only ‘established contact’ with the enemy. So, in the end, I announced over the radio: 'attack concluded', and 'courier in curtains' (enemy aircraft in the clouds). As we learned later, ground control had heard: ‘courier terminated’.

When we returned to home base, we were feeling so terrible that we hardly dared to land. Back on the ground (at 20:37 h), we hoped the ground would open up beneath us and swallow us whole, but soon the bus arrived to pick us up. We thought: “Damn, we’re in for it now”, but there was none of that. We had only just arrived at the control tower when Major Lent and Hptm. Ruppel approached us and congratulated us on our first victory! We were flabbergasted, until we heard the reason why. 20 minutes before he himself would claim his 50th nocturnal victory, Major Lent had seen ‘our’ Tommy dive down from the clouds and crash into the sea, engulfed in flames. This was also confirmed by observations from the Hering sector. We were relieved and happy, of course. For our first victory, we were awarded the Iron Cross 2nd Class by our commander. To achieve this, we had used 80 cannon shells and 1,250 machine gun rounds.

Fw. Erich Handke. (Coll. Melvin Brownless)

The Kraft/Handke crew would eventually have to wait until 24 September 1944 before having their first victory officially awarded. By then, Georg Kraft had been dead for 13 months; he died in August 1943. Their opponent was Lancaster W4340 from the 103 Squadron that, returning from Essen, disappeared into the sea 40 km north of Den Helder at 19:52 h; the crew of 7 is still listed as missing. Major Helmut Lent, Kraft’s and Handke’s commander, shot down a Wellington minelayer at 20:11 h in the Schlei (Schiermonnikoog) sector, which crashed into the sea 30 km north of Schiermonnikoog. The entire crew is also still listed as missing. It had been another bloody night in the Wadden area.

Victim of Marine Flak. During a minelaying operation in the night of 18 to19 February 1942, the 420 Squadron Hampden AD915 was caught in searchlights on Borkum and shot by the 6th battery of the M. Flak Abt. 216 on the island. At 22:05 h, it attempted a botched emergency landing on the North Sea beach of Schiermonnikoog, claiming the lives of 2 of the 4 crew members. (Coll. Wijb-Jan Groendijk)

The Halifax near the pier of Harlingen

At 26 minutes past midnight on 20 September 1943, the Halifax DG252 from the 138 Squadron, coming from the north, flew at low altitude towards the harbour of Harlingen. The 138 Squadron carried out special missions; the DG252 was probably ordered to drop weapons for the Dutch Resistance. The Halifax flew right into a hornet’s nest: 11 minutes prior to this, the anti-aircraft alarm had gone off in Harlingen because the sound of British aeroplane engines had been heard and the German Navy authorities had readied the Flak installations in Harlingen as a cautionary measure. The next day, the light Flak units from the Marine Flak Abt. 246 in Harlingen issued this report:

“There was a full moon and unobstructed views up to 5 km. The aircraft was immediately recognised as a four-engine enemy Halifax, caught in the searchlights of tactical installation no. 4/25/101 and 4/25/102 and shot by tactical installation no. 4/5/1 with twenty 2 cm shells. The shots all found their target: hits to the cockpit of the bomber were seen. Smoke emerged from the aircraft, which quickly lost altitude, hit the head of the pier with its left wing and crashed into the water about 50 metres north of that position at 00:28 h, breaking into pieces upon impact. After approximately 4 minutes, the aircraft disappeared under the water.

During the attack, the enemy aeroplane fired at searchlight installation 4/25/101. It did not suffer any hits; the bullets impacted in front of the installation and no-one was injured. A harbour patrol ship and a toll ship immediately sailed to the crash site, which was marked by two small rubber boats. One of these rubber boats and a large number of parts from the wreck were salvaged. The rubber boat itself was empty. Around 8 am, a corpse was found floating near the crash site.” (This was navigator F/O James Brown).

On 27 September 1943, the following was added:

“The exact position of the enemy plane crash has been established. A diver from Wilhelmshaven has salvaged part of the plane’s hull; large amounts of propaganda materials were found inside, which have been confiscated by the Luftwaffe for further analysis. During the following weeks, the other parts of the wreck will be salvaged.”

Pilot Officer George A. Berwick DFM, the 26-year-old flight engineer from the 138 Squadron Halifax DG252 together with his wife Elizabeth (Betty) Berwick. (Coll. Sandra Uden, via Kelvin Youngs/ aircrewremembered.com)

S/Ldr Wilkin and his crew of four, all of them highly decorated veterans, lost their lives at the pier of Harlingen. Navigator F/O James Brown was buried in Harlingen. Canadian pilot Richard Pennington Wilkin washed ashore on Terschelling in the middle of October 1943 and was buried in West-Terschelling. P/O George Alfred Berwick (the flight engineer) was found near Pietersbierum and also interred there, and F/O Hugh Burke (radio telegrapher) washed ashore on the sea dike of Ameland southwest of Nes, where he was laid to rest on 11 October 1943. Only tail gunner F/Sgt Albert Hughes does not have a known grave and is listed as missing.

Situation map of the shooting of the 138 Squadron Halifax DG252 on 19-20 September 1943 in the harbour of Harlingen by the 1. M. Flak Abt. 246. These situation maps were drawn up meticulously as a standard by the unit responsible for the shooting, to later be used as evidence and be awarded a victory by the German authorities. (Coll. BA/MA, RM122-413)

A Halifax bomber, the type of aircraft that was shot down near Harlingen. (Coll. Tony Hibberd)

Convoy strikes and Gardeners in the Wadden

The battle for the German maritime convoy routes

Read more →